Warning: Spoilers for ‘Saltburn’ ahead

On the 19th October 2022, a vote on fracking in the Houses of Parliament descended into chaos. The Conservatives’ Liz Truss, who would go on to become Britain’s shortest-lived Prime Minister, had intended to use the vote as a ‘confidence measure’ and had ordered a three-line whip for her own party to reject the Labour motion, at the risk of her own government collapsing.[1] Long-accustomed the British have become to an overarching sense of political chaos and turmoil post-2016[2]; yet, the scenes that unfolded that night stand out as particularly tumultuous and, indeed, farcical, which was evidenced by the anger of Conservative MPs regarding the handling of the vote. Backbencher Charles Walker gave an extraordinary interview with the BBC in its wake, demonstrating his anger and derision with the parliamentary Conservative Party not only in the handling of the vote, but in their orchestration of Truss’ ascension to the leadership, and thereby Prime Ministership, as a whole:

‘This whole affair is inexcusable [sic.] it is just a pitiful reflection on the Conservative parliamentary party at every level […] this is an absolute disgrace. As a Tory MP of seventeen years who has never been a minister, who has got on with it loyally most of the time, I think it is a shambles and a disgrace. I think it is utterly appalling. I am livid and, you know, I really shouldn’t say this, but I hope all those people who put Liz Truss in Number 10, I hope it was worth it. I hope it was worth it for the ministerial red box, I hope it was worth it to sit around the Cabinet table because the damage they have done to our party is extraordinary […] I have had enough of talentless people putting their tick in the right box not because it’s in the national interest but because it is in their own personal interest to achieve ministerial position’.[3]

Since its modern inception after the 1832 Reform Act that extended voting rights in Britain, the Conservative Party, also known as the Tory Party, has championed the interests of law and order, landed interests, trade and national identity. It has also had a concerted paternalism about it; a sense that the people of the party were in some way born to rule as ‘the political arm of the rich and powerful’ with so many Tory MPs and Prime Minsters hailing from extremely wealthy backgrounds, predominantly attending private schools and Oxbridge.[4] I visited Oxford in January 2024 and found the place oozing with this bizarre sense of tradition and self-congratulatory prestige, not least when our tour guide described the seemingly endless stand-offs between the students of the university and the townsfolk, who, for a few hundred years, seemed perpetually embroiled in a class-turf war. I came away thinking that the University of Oxford was a natural Tory breeding ground; with the arcane rules, rituals and traditions, its exploding coffers and pervasive sense of superiority, it’s hard to imagine anyone coming up with any new ideas there.[5] It may be first in the Time Higher Education World University Rankings, it may have a ‘Gold’ rating in ‘Teaching Excellence Framework’, whatever these arbitrary ratings actually mean, but in a place where the statue of Cecil Rhodes continues to cast a violent colonial gaze over all who pass in the vicinity of Oriel College, with nothing more than an explanatory plaque to problematise his presence, it would appear that conservatism, tradition and entitlement still hold sway here.[6]

Charles Walker MP did not go to the University of Oxford. He was educated privately, like many Tory MPs, but then unlike many of his colleagues, he chose to study at the University of Oregon instead of pursuing the proverbial Oxbridge route. However, his analysis of his own political party, seething and scathing in equal measure, is also illuminating, with his admonition that he has ‘had enough of talentless people’ standing out as particularly pertinent. He seems entirely fed up with members of his party who have made self-motivated political decisions to increase their own reach and power, choosing to court favour with the weathercock of the day over a greater sense of collective good; people who prioritise themselves but ultimately have no real vision, plan or, seemingly, basic ideology that serves as their driving force, flip-flopping their way through their political careers and the UK’s subsequent political hellscape.

And, thus, we come to Emerald Fennell’s Saltburn, the director herself an alumnus of the University of Oxford. Saltburn is film that people have, seemingly, come to love to hate and that, I argue, has suffered some misunderstanding. There have been many accusations levelled at it, the most pervasive being that ‘it doesn’t mean anything’, or that it was trying to be another film but didn’t quite get there (‘the implied film is better than the actual one’), or that it’s symptomatic of film’s dance with death via social media. As someone who has, despite my Derridean critical education, often sought out the ‘meaning’ of texts, even if it’s just being secure in what I think a text means, I was pleasantly surprised to realise that I was not one of this group challenging Saltburn for not meaning enough, or anything at all. I observed that the film nodded to eat-the-rich films like Parasite, with references to moths and images of critters that bejewelled the end credits; yet, despite these nods, it did not feel like this was the overarching idea of the film. However, this is clearly what many people wanted and have since imposed on it. One of my favourite video essayists, Broey Deschanel, analysed Saltburn in direct comparison with The Talented Mr Ripley, arguing very astutely that Ripley’s interrogation of class is far superior to Saltburn’s, and that Matt Damon’s portrayal of Tom Ripley as both maniacal and wounded juxtaposed with the grotesque entitlement of Jude Law’s Dickie Greenleaf forms one of the key dramatic tensions of the film that cements this class analysis. I think, however, that she actually hit the nail on the head with the title of her video to describe Saltburn as a wholeand, perhaps, its main character Oliver Quick played by Barry Keoghan: ‘The Untalented Mr Ripley’. Untalented indeed. That may just be exactly the point that people are looking for: this film is about Charles Walker’s ‘talentless people’.

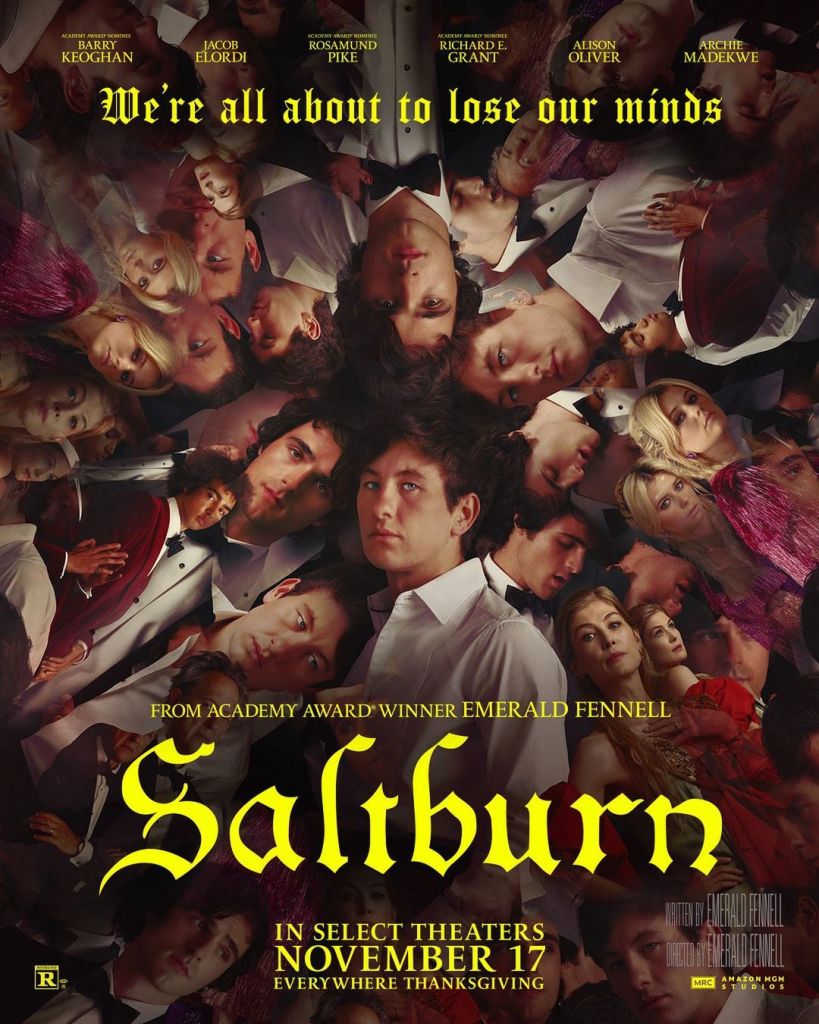

For me, Saltburn is a quintessentially British film about the state of Britain, walking in the footsteps of Trainspotting, Billy Elliott, I, Daniel Blake and others. One of the film’s promotional posters reads: ‘We’re all about to lose our minds’. Anyone recovering from what we have observed and experienced as an electorate in Britain, particularly in the wake of 2016, could be forgiven for thinking: ‘Yes, quite’. Former BBC Political Editor Laura Kuenssberg, in my mind not an entirely unproblematic journalist, made a comprehensive documentary charting the tumultuous succession of crisis-ridden Tory governments in the years following the referendum to leave the EU and it makes for ‘gruesome’ watching in the words of journalist Rebecca Nicholson.[7] Called ‘Laura Kuenssberg: State of Chaos’, the series walks us through the fallout of Britain’s vote to leave the EU.[8] Despite living through it and witnessing all the twists and turns, there is something mind-blowing about seeing the true scale of upheaval mapped out for us, with commentary from civil servants, politicians and journalists who navigated it and orchestrated it. We see five Prime Ministers change hands (David Cameron, Theresa May, Boris Johnson, Liz Truss, Rishi Sunak); back-stabbing and in-fighting within the government in the midst of Brexit negotiations; Boris Johnson’s illegal proroguing of Parliament, which I referenced in this essay; the shambolic handling of the Covid-19 pandemic in the UK, including the Partygate scandal that undermined social distancing measures and the extortionate contracts given to Tory grandees and connections who offered dysfunctional track and trace systems and PPE in exchange for millions of pounds; the sinister rise and fall of unelected officials like Dominic Cummings who was given so much power by Boris Johnson that he was able to stage his own press conference in the rose garden of Downing Street to defend his behaviour in the Barnard Castle debacle; the collapse of the Liz Truss government after 45 days against the backdrop of the country’s longest-reigning monarch passing away; the ascension of Rishi Sunak, seen as a ‘safer pair of hands’ than the volatile Boris Johnson but who was the architect of one of the most ridiculous pandemic schemes ‘Eat Out To Help Out’ which helped to drive up new Covid-19 infections.[9] In short, it is has been an unbelievable, disorientating time in British political history.

Whilst many people have wanted Saltburn to be a searing critique of class inequality that skewers the rich, I think this film, whether it meant to or not, exposes two big political archetypes that have been and continue to be extremely prevalent in British politics and culture more generally, as outlined above: primarily, the rotting, ineffective ideologically conservative ruling class who for so long have extracted wealth and wallowed around in it, whilst believing in their God-given right to lord themselves over others but ultimately do nothing and have nothing to offer society; secondly, the middle class aspirers we can’t help but look to to dismantle class inequality who seemingly just want to, and eventually become, what we thought they wanted to rip down. This is a film about talentless, self-interested people who want to maintain their power; in many ways, it is a satire of the maddening and chaotic state of British party politics.

Much of the discourse online around this film conveys the sense that people wanted this to be a film about class war. What we got instead was a somewhat trashy film that enjoyed rollicking around in its own sense of scandal. The film seemed to achieve this, partially, through its apparent enjoyment of irreverently wallowing in the mess, sensuality and abjectness of the human body: we have the iconic ‘bathwater’ scene, where Keoghan’s Oliver Quick slurps up Felix’s used bathwater into which he has just ejaculated; the cunnilingus scene where Oliver goes down on Ventia whilst she’s mid-way through her period, the grave scene, Oliver Quick’s antler outfit to name just a few. There seemed to be little political messaging lurking in the background beyond the fact that these scenes were meant to be provocative and shocking, which left some reviewers like they had been ‘shoehorned’ in to redeem the plot.[10] However, for me at least, there is something delightfully trashy about them; and I don’t mean that in a way to disparage the film. I mean ‘trashy’ with the same sort of respect and affection I hold for shows like ‘Gossip Girl’ and ‘The Real Housewives’ franchises. Throughout the film, the characters thrive in their relentless gossiping about other characters and these shadowy, shocking scenes have managed to cultivate the same kind of discourse around the film itself; a discourse tinged with delicious salaciousness. Additionally, it is reminiscent of the British’s suspicions, long held, that some members of the privileged upper classes have involved themselves with these kinds of shenanigans, despite their crisp and staid appearances. Are the actions depicted in Saltburn anymore scandalous than 2015’s ‘Piggate’ allegations? A scandal fuelled and propagated by Lord Michael Ashcroft in what appeared to be a stab of revenge at then-Prime Minister and current Foreign Secretary Lord David Cameron, who he claimed got up to all sorts of licentious porcine activities as a member of the mysterious Piers Gaveston Society at the University of, you guessed it, Oxford.[11]

As such, Saltburn’s trashiness (again, I want to emphasise that I do not use this term in a way to undermine or disparage the film!) gives way to the first political archetype; many of these characters are facsimiles of upper class people who are relatively two-dimensional but who relish in the power and prestige of their ancestry, their landed wealth and their proximity to those they hold close and delight in savaging. This is famously evident in Rosamund Pike’s character Elspeth who delights as much in gossiping about other people as she does in covering up the fact that she has been gossiping about other people. She casually reprimands Farleigh for telling Oliver that ‘we were just talking about you’, which, indeed, they had, by telling him without missing a beat that he makes up ‘the most awful things’ and that ‘of course we weren’t’. They are a group of people who don’t actually want to immerse themselves in critical, intellectual inquiry but would rather stew in their fantasies and speculations about other people’s lives, which Elspeth, again, cements when she quips later on in the film that Pulp’s song ‘Common People’ could not have been about her because the young woman depicted in the song ‘came with a thirst for knowledge’ but she ‘never wanted to know anything’. The limited knowledge of Liverpool they display in their first dialogue about Oliver is a good demonstration of this: Liverpool has long been a city that has attracted snobbery and condescension throughout the UK, with everything from the Scouse accent, fashion and beauty trends and implied poverty of its inhabitants offered up to ridicule and dismissal in equal measure. Elspeth and her friend Poor Dear Pamela draw on typically classist stereotypes about the city in their speculation about Oliver’s upbringing, for example imagining Oliver’s hometown Prescot on Merseyside as ‘some awful slum’, and with Pamela asserting that ‘I think that’s actually rather normal when you’re poor; when you’re poor that sort of thing happens a little more’ when Elspeth ravenously chews over the image of Oliver putting his fingers down his alcoholic mother’s throat to make her sick. The family delightfully indulges in both pity and scorn for Oliver that fuels their own sense of civilised superiority, choosing to lean into macabre fantasises about his poverty to cushion and closet themselves quite happily within their privilege.

However, it is this that makes them vulnerable. Whilst the film tracks each individual Catton being picked off by Oliver, the Cattons clearly play the same game, with the weakest link in their midst subjected to the same scorn, ridicule and exclusion. Primarily, when Poor Dear Pamela, who morosely tells Oliver at dinner that ‘Daddy always said I’d end up at the bottom of the Thames’ does go on to die, Elspeth’s wickedly dark response is that ‘[Pamela]’d do anything for attention’. Then, once he too has outstayed his welcome, Farleigh is ejected from Saltburn without ceremony. There is no loyalty among the upper echelons at Saltburn, and this is something we have seen played out politically in the current government, with the endless leaks, scheming and backstabbing that have entailed Tory party politics, particularly post-2016. This has been born out of a political culture of self-aggrandizing, which Charles Walker highlighted with such vehemence in 2022, but was also raised by the outgoing MP for Maidenhead and former Prime Minister Theresa May herself in her final speech to Parliament on the 24th May 2024 before its dissolution in the wake of the up-coming General Election. Whilst almost endearingly referring to her ‘place in history’ as the only MP for Maidenhead as a result of her holding of the post of MP there for 27 years, which charts the establishment of the constituency to its boundary changes in 2024, more than, perhaps, her more historical tenure as a Brexit Prime Minister, May was also critical of self-serving politicians. Not only did she make light of being in government and members of her own side not voting with her on three separate occasions, but she emphasised the role and responsibility of MPs to represent constituents, with her worry that ‘there are too many people in politics who think it is about them, their ambitions, their careers and not the people they serve […] their job here is not to advance themselves but to serve the people who elected them’.[12] Here, she is speaking of the same genre of ‘talentless’ people who prioritise their own politicking over a sense of humility in their service on behalf of their constituency. We know that in Saltburn the natural conclusion of so much selfishness and self-investment is implosion and a group of people rotting from within, with, of course, a little help from Oliver Quick. Yet, the delight with which they rip into their social inferiors and one another to maintain their own position points to a self-inflicted form of violence that marks their own undoing. We will have to see if such a political culture the Tories have exhibited over the past few years will ring in their own death knells of being in government, which only Thursday 4th July 2024 will reveal.

This leads to my second British political archetype that Saltburn demonstrates: the pretender. In this, we have the character Oliver Quick, who delivers the twist that isn’t a twist: whilst peddling the story of being a disadvantaged, impoverished student from Merseyside to ingratiate himself with Felix Catton, he actually hails from a comfortable middle-class home. Like many people who have benefitted from privilege and wealth, Oliver leans on a narrative of working-class hardship and meritocratic achievement to make himself an object of sympathy, with his Merseyside upbringing a particularly astute geographical choice on the part of Fennell thanks to its working class heritage.[13] Many people watching the film felt that this ‘twist’ lacked punch, but, if you have been paying attention to British politics, there is something purposefully unsurprising about it. He used this tactic because it works, has worked and is commonplace in modern British politics. In Britain, many politicians have used working class allusions in their self-fashioning to make themselves more appealing and sympathetic in the eyes of the electorate. We have seen this even in the names that politicians opt to use for themselves, with former Prime Minister Anthony Charles Lynton Blair opting for ‘Tony’; former Chancellor of the Exchequer Gideon Oliver Osborne opting for ‘George’ and former Prime Minister Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson opting for ‘Boris’ as three standout examples. All attended private school and all, you guessed it again, attended the University of Oxford. What these examples also convey is that this happens across the British political spectrum; whilst many would question Tony Blair’s left-wing credentials, particularly in light of Margaret Thatcher referring to him as one of her biggest achievements, the fact that he used the optics of a working-class name to mask his privilege to leverage support is significant.[14] Crucially, especially when this tactic is used by politicians on the Left, there is the real threat of upper middle class politicians using the power they have garnered from appealing to working class voters to then ‘ape the aristocracy in their modes of life’, becoming what they have sought to resist and neglecting those who put them there, something Marx and Engels keenly observed particularly in the English middle classes: ‘By this means the middle class roused the working classes to help them in 1832 when they wanted the Reform Bill, and, having got a Reform Bill for themselves, have ever since refused one to the classes—nay, in 1848, actually stood arrayed against them armed with special constable staves’.[15]

And is Oliver Quick anything other than an ‘ape’ of the aristocracy? Throughout the film, we see him aping the role of a working class student at Oxford, aping Felix Catton as their friendship grows, symbolised through the strategic use of a Jack Wills hoody (a signifier of an attempted to nod to the British gentry, if there ever was one), aping the ‘Brideshead Revisited’ chic of black tie whilst at Saltburn, aping a Ripley-esque psychopathic figure when really he is just as talentless, selfish and whiney as the rest of them. It is in this that critics’ comparison to Ripley doesn’t quite hold water for me; the psychological manipulative mastery of Ripley comes up against the cynical apery of Oliver Quick, making these two characters very unalike and doing very different things. Time will tell if Labour’s latest pretender, in the form of Kier Starmer, will emerge victorious in the up-coming General Election. His name evokes the founder of the Labour party Kier Hardie and he has already harked back to his father’s humble working-class occupation as a toolmaker on the campaign trail. This, despite his own selective grammar school education before his attendance at the University of Leeds and postgraduate study at, here it comes again, the University of Oxford. Starmer has a history of socialist activism, and yet has clearly manoeuvred the Labour party away from the Left and into a more Centre position, verging on centre-right, as the party of Tory voters who are sick of Rishi Sunak but not as extreme as to vote for Reform UK. With a huge focus on defence and immigration, and watering down environmental policy, the Labour party is clearly aping the traditional policy areas of the Tories, which is evident in their increasing popularity outside progressive urban strongholds, where their vote share in recent local elections decreased.[16] Labour’s apery is also evident in Laura Kuenssberg’s observation that the unfolding so-called ‘purge’ of left-wing influence in the Labour party, in particular in regards to the treatment of veteran MP Diane Abbott, ‘stands in awkward contrast to the way a string of Tories, including Natalie Elphicke, Dan Poulter and Mark Logan, have been welcomed into Labour with open arms in recent weeks’.[17] So far, so Oliver Quick: the backstabbing akin to the Tories, as previously discussed, and the cynical embrace of right-wing idealogues in an attempt to woo voters appears as a bid to obtain power at any price, thus leaving a particularly sour taste in the mouth. How can a party that has its roots in the socialist tradition now find itself as an attractive prospect for disaffected Tories? Precisely because under Kier Starmer, the party has become so adept at aping the Tories. At this point, it feels like a Labour victory in July, a victory so many on the Left have yearned for over the past 14 years, will be as thrilling and as sickening as Oliver Quick’s naked dance through the cavernous, empty halls of Saltburn: Starmer’s own dance down the corridors of Downing Street may feel equally as fabulous after 14 years of opposition, but also equally as hollow.

Saltburn is not what many people clearly wanted it to be: it is a trashy, scandalous, cynical piece of film-making that more than offering a critique of Britain’s class system serves to satirise it. Those who wanted something akin to Parasite or The Talented Mr Ripley are, I am sure, disappointed. But for me, Saltburn reflected the confounded state of British politics; the unbelievable, disturbing, riveting hilarious horror of the state of our democracy. It is rare for me to adopt the lens of ‘Britishness’ when writing a critical essay (I worry that it veers me towards some sense of nationalism of which I am very wary). Yet, for me, this is exactly what this film is about. ‘I don’t know what’s OK anymore’, a friend said as we left the cinema hooting and quaking in equal measure after a group trip to see the film. If this doesn’t perfectly capture the impact of a political system presided over by ever so many talentless people, then I don’t know what does.

[1] https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2022/oct/19/crunch-commons-vote-on-fracking-descends-into-farce [accessed 08:23, 2nd March 2024].

[2] ‘Laura Kuenssberg: State of Chaos’ BBC iPlayer https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episodes/m001qgww/laura-kuenssberg-state-of-chaos

[3] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/uk-politics-63320605 [accessed 08:36, 16th March 2024].

[4] Chavs, Owen Jones (London: Verso, 2012), p.40.

[5] https://www.theguardian.com/education/2018/may/28/oxford-and-cambridge-university-colleges-hold-21bn-in-riches [accessed 08:22, 16th March 2024].

[6] https://www.ox.ac.uk/sites/files/oxford/Oxford%20University%20Financial%20Statements%202022-23.pdf [accessed 08:29, 16th March 2024]; https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-oxfordshire-58885181 [accessed 08:29, 16th March 2024].

[7] https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2023/sep/11/laura-kuenssberg-state-of-chaos-review-full-of-extraordinary-revelations-if-you-can-bear-to-watch [accessed 17th March 2024, 09:03].

[8] https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episodes/m001qgww/laura-kuenssberg-state-of-chaos [accessed 17th March 2024, 09:10].

[9] https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/economics/research/centres/cage/news/30-10-20-eat_out_to_help_out_scheme_drove_new_covid_19_infections_up_by_between_8_and_17_new_research_finds/ [accessed 17th March 2024, 09:32].

[10] https://www.bfi.org.uk/sight-and-sound/reviews/saltburn-ostentatious-black-comedy-designed-shock [accessed 28th April 2024, 11:29].

[11] https://time.com/4043311/david-cameron-pig-gate-scandal/ [accessed 28th April 2024, 12:42].

[12] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-_xZrdoP5rQ&ab_channel=PoliticsJOE [accessed 31st May 2024, 15:04).

[13] https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/society/2022/04/a-quarter-of-britons-paid-100000-or-more-identify-as-working-class [accessed 1st June 2024, 13:14].

[14] In 2002, twelve years after Margaret Thatcher left office, she was asked at a dinner what was her greatest achievement. Thatcher replied: “Tony Blair and New Labour. We forced our opponents to change their minds.” (Conor Burns, April 11, 2008) https://economicsociology.org/2018/03/19/thatcherisms-greatest-achievement/ [accessed 1st June 2024, 15:55].

[15] Marx and Engels Collected Works, Volume 13 (pp.663-665), Progress Publishers, Moscow 1980 https://marxengels.public-archive.net/en/ME1912en.html#N464 [accessed 1st June 2024, 13:42].

[16] https://www.theguardian.com/politics/article/2024/may/03/labour-celebrates-victories-but-loses-ground-in-urban-and-heavily-muslim-areas [accessed 1st June 2024, 15:07].

[17] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c7220exjzvno [accessed 1st June 2024, 15:12].

wow!! 91‘Saltburn’: A delicious and disturbing British classic

LikeLike