As it does for many students, the third year of my university degree course entailed an extended independent project: a culmination of two and a half years building academic expertise in research, negotiating criticism and secondary material, deep and thoughtful analysis of language all framed within the construction of an elegant yet convincing argument. Whilst my department opted for a 7000-word long essay over a dissertation of 12,000-15,000 words (with one staff member morbidly commenting that they didn’t want to give students ‘too much rope with which to hang themselves’) it was still a rigorous task that began with a scintillating and frightening proposition: what on earth to write about?

Making any kind of decision for me initiates a period of profound reflection and soul-searching: I spent my early twenties distracting myself and others no-end with ‘Which Disney princess are you?’ Buzzfeed quizzes (answer: Pocahontas), and making a collage ‘All About Me’ at work a few years ago triggered something of an existential crisis. Before eventually deciding to write my long essay on the concept of ‘nothing’ in the elegiac and ekphrastic poem ‘Phantom’ by Don Paterson, a topic I picked the day before the deadline for submitting the topic, I was in torment trying to work out what I wanted to write about. I landed on a number of different options which, compounding my own purgatorial sense of ‘who am I and what shall I write about?’, were batted away by various academics.

These included one idea I had about the number three appearing in folklore (I still don’t understand the reservation about that one; Freud’s ‘Theme of the Three Caskets’ was going to anchor the thing, and my subsequent interest in Jungian analysis would open up my ideas in numerous different ways). Similarly, and most relevant for this essay, was an idea I had about cinematic adaptations of ‘Wuthering Heights’, and why, in my opinion, they never seemed to work. Another tutor dissuaded me from this task, citing either Queenie Leavis or Virginia Woolf in an attempt to communicate his perception that this topic was somewhat juvenile and I should do something more mature.

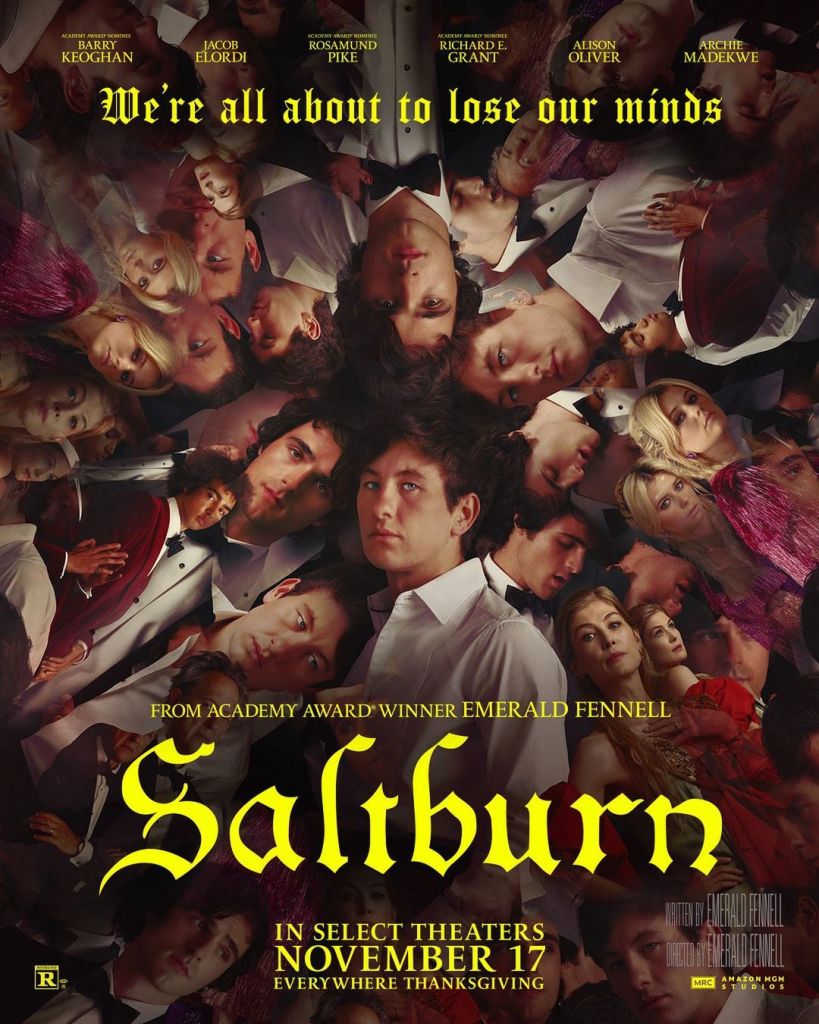

With the news that Emerald Fennell is writing, producing and directing a new adaptation of Wuthering Heights, which started production in 2025, I have decided to return to my juvenile project. Instead, however, of performing a deep-dive into the adaptations that have come before, I will consider what I hope will emerge in this new adaptation. There has already been plenty of comment and controversy surrounding the casting of her adaptation – Margot Robbie and Jacob Elordi would certainly not have been my choices for Cathy and Heathcliff, and I think many others agree – but I want to focus more on what I hope to see: which characters will be given prominence, will all of the idiosyncrasies, physical violences and clipped unhinged moments of the novel – biting, blows, ravings, hair-pullings – be woven in?

The first place to start was with re-reading the novel, which I did in the summer of 2024 in the waning months of pregnancy. The last time I read Wuthering Heights was when I was eighteen and studying it alongside Milton’s Paradise Lost and Webster’s The White Devil for A-Level. Back then, Gothic themes were prevalent not just in my studies but in noughties teenage culture at large, with the figure of the vampire in particular famously resurging in the Twilight novels and subsequent films, weekly doses of The Vampire Diaries on ITV2 and its spin-off The Originals, and True Blood for a more risqué proponent of the genre. The Noughties vampire craze is certainly something worth exploring in and of itself, and whilst I wasn’t the most adamant Twi-hard, I was certainly enamoured with the Gothic’s propensity for danger and romance. Wuthering Heights was no exception, with the emotional melodrama from all and sundry, the family saga and the theatricality of the various settings, from the Yorkshire moors to the two homesteads of Wuthering Heights and Thrushcross Grange. These are all, undoubtedly, kindling for the teenage imagination, which became ever so apparent upon returning to the text as a heavily pregnant 32 year-old woman. I am curious to see if Fennell’s new adaptation will ring in a new wave of Gothic story-telling, perhaps already begun with the re-make of Nosferatu and Ryan Coogler’s Sinners, and what that will tell us about the cultural moment in which we find ourselves.

Wuthering Heights remains a vivid and dramatic novel, with every character demonstrating a degree of emotional dysregulation, impetuousness and violence; characters I raged alongside as a teenager but now seem astonishingly unhinged in that unnerving, hopeless, hilarious and deeply endearing way that adolescents often are. This is because much of the action is being played out by just them: teenagers. As adaptations of The Great Gatsby are in danger of following Nick’s cue and romanticising its protagonist and anti-hero Jay Gatsby, adaptors of Wuthering Heights are in danger of imbuing this novel, and its key protagonists Catherine Earnshaw and Heathcliff, with a sage maturity that is not adolescent when it really should be.

After all, this novel does not start with the mad entanglements and upheavals of the Earnshaws, Lintons and Heathcliffs, with the relationship between Catherine Earnshaw and Heathcliff in particular eclipsing most of the rest of the novel’s drama in our collective imagination. The novel, in my mind, starts at ‘the sea-coast’ with a pompous, avoidantly attached man who shrinks ‘icily into [himself] like a snail’ when the girl onto whom he has heaped attention starts to return his affection, causing her to ‘doubt her own senses’ and leave with her mother.[1] In the aftermath, and fancying himself a misanthrope who wants to remove himself from society, he decamps to Yorkshire and arrogantly plunges himself into the company of Mr Heathcliff, his new landlord. It is through him, Mr Lockwood, that Nelly Dean’s history of the families of Wuthering Heights and Thrushcross Grange emerges.

Adaptation, like translation, is an art form in and of itself, and it is inevitable that changes and modifications to a literary text are made when it is fashioned from, in the case of Wuthering Heights, a novel into a film or television screenplay. The end goal cannot be to lean into translating the novel too literally for the screen; however, the success of the novel, I argue, relies as much upon its structure as it does on its characterisation, and to do away with any sense of framed narrative, the sense of a story-within-a-story that is created through the use of Lockwood and Dean, erroneously indulges and intensifies the most melodramatic parts of the work. I want to see an adaptation of Wuthering Heights that makes much of these two and the containment they provide. For, in my mind, Wuthering Heights is not a psychological novel, even though the psychology of the characters is absolutely central to the development of the plot, with trauma, addiction, grief, abuse and emotional breakdown all exhibited. Without minimising the severity of any of these, I still see Wuthering Heights as Gothic adolescent drama; what elevates it to greatness as a novel is through its considered structure, the theatrical blocking of various scenes – the various entrances and exits of characters between rooms and locations reads almost like a play – and the way in which Bronte skilfully maps pathos onto a most singular and evocative environment: the Yorkshire moors. Personally, I am thrilled that we are not in the heads of Catherine Earnshaw, Heathcliff, Hindley, Catherine Linton and Linton Heathcliff and whoever else. These characters are so erratic, dogmatic, cruel and selfish that we absolutely need distance from them. Bronte’s genius is that she gives us two characters, Lockwood and Dean, who are two imperfect filters for the chaos and sheer ridiculousness of the rest of the characters: they make Catherine, Heathcliff and Hindley et al. bearable, but they do not hold a sense of moral superiority over them.

Primarily, far from being a vacant empty vessel of character into whom the story is poured, as one might argue Captain Walton is in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Lockwood is consistently presented as creepy, malevolent, egotistical and, yes, ridiculous. He presumes to visit Heathcliff at the start of the novel and before much happens gets into a scrap with some dogs after ‘winking and making faces at them’, driving the bitch, and seeming matriarch of the pack, to break into ‘a fury’, leaping onto him and inciting the others to ‘assault’ his ‘heels and coat-laps’, thus requiring him to fend them off with a poker before calling for help.[2] Here, Bronte presents a scene of buffoonery that is also laced with something sinister, as buffoonery often is: Lockwood offers no culpability, explaining his decision to make faces, which caused the ruckus, with an entitled degree of passivity – ‘I unfortunately indulged’ – as though it wasn’t completely his fault for winding them up. As such, within the first couple of pages, our narrator is presented as a ghosting fuckboy who wantonly upsets women, and I like to think of the bitch as some retributive symbol for the girl he messed about at the seaside.[3] Bronte continues her characterisation of Lockwood as a man who is conceited towards the workers at Thrushcross Grange, affronted as he is by prescribed mealtimes (‘a matronly lady taken as a fixture along with the house, could not, or would not comprehend my request that I might be served at five’) and a ‘servant-girl’ cleaning a fireplace and ‘raising an infernal dusk’; and who takes a predatory interest in young Catherine who he describes as ‘scarcely past girlhood’ but who is physically ‘irresistible’ and ‘exquisite’.[4] Indeed, later on in the novel he pursues his interest in young Catherine indirectly, revealing to us that he ‘should like to know [the] history’ of ‘that pretty girl-widow’ and remonstrances himself with regards to her personality: that he should ‘beware of the fascination that lurks in Catherine Heathcliff’s brilliant eyes. I should be in a curious taking if I surrendered my heart to that young person, and the daughter turned out a second edition of the mother!’[5] Here, we see one of the many instances that Bronte provides of his predatory and wolfish behaviour, with repeated reflections that dwell on her physical appearance and his consistent overestimation of his own desirability.

As such, we can see that Lockwood is as dogmatic and deluded as many of the other characters. I would argue that his name also reflects this, with the image of ‘lock’ hinting that there is something extremely limited and limiting in his social ineptitude, that his perspective is unmoving and even, perhaps, that there is something in his nature that is controlling and desires to dominate, something that Heathcliff appears to be drawn to in the first chapter, loosening up and relaxing into ‘a grin’ as he does when Lockwood threaten to enact violence on the dogs: ‘If I had been [bitten], I would have set my signet on the biter’.[6] It is this fixedness that ultimately makes him the perfect character to dream Cathy’s visitation in Chapter 3: he is outsider enough to be unfamiliar with the family history and, thereby, experiences the full terror of the ghostly child at the window, and his cynicism and pragmatism about the presence of a ghost or a spirit, even in the dream realm, makes it all the more believable that the past has an almost supernatural presence in the lives of the living at Wuthering Heights. Lockwood is perplexed and perturbed at Heathcliff’s sobbing and crying out for Cathy, remarking that ‘there was such anguish in the gush of grief that accompanied this raving, that my compassion made me overlook its folly, and I drew off, half angry to have listened at all, and vexed at having related my ridiculous nightmare, since it produced that agony’.[7] He is convinced that nothing actually happened, with his reference to Heathcliff’s ‘folly’ and ‘raving’, clearly showing his belief that Heathcliff is acting irrationally and is annoyed at himself for having stoked it by relaying his dream. He doesn’t want to feed the psychodrama that is playing out in front of him and promptly leaves, taking us with him, and is drawn into it only in so much as he feels embarrassed and guilty by, what he perceives to be, Heathcliff’s extreme emotional response and the part he played in exacerbating it. In a novel teeming with emotional outbursts, we need Lockwood as this container of the chaos, and I think an adaptation’s success relies on it too.

Of course, Lockwood is not alone in his containment of the drama: Bronte teams him up with Nelly Dean in the relay of the tale, thus ensuring the essential distance we feel from the emotional tumult. These two characters become ‘companionable’, not only in the way in which they spend time almost cosied up storytelling together in the novel, but through Bronte’s use of them to construct and elevate the drama of the novel itself.[8] They are essential. Like Lockwood, Bronte presents Nelly as removed enough from the action and entanglements of the main characters by tracking her movements beyond the others, but she is inherently bound up with them too and is, thereby, able to deliver and weigh in on the emotional upheaval, because it is partly hers too. This is most evident in the scene in Chapter 17 where Doctor Kenneth relays Hindley’s death to her and knows that she’ll need to ‘nip up the corner of [her] apron’ for the tears that will come, which they do. He reflects that Hindley died ‘barely twenty-seven […] that’s your own age; who would have thought you were born in one year?’ To which Nelly responds that ‘ancient associations lingered’ around her ‘heart’ and she ‘sat down in the porch, and wept as for a blood relation’.[9] This scene reminds us that Nelly is relatively young and not the matronly or even crone-like figure that she has embodied in the cinematic imagination. Whilst she tends to Cathy, Heathcliff and Hindley as almost a nurse when they are young, for example when they all fall ill with measles, we are reminded of the fact that she is practically one of them by Bronte not only having her describe how she played with them before Heathcliff’s arrival, but in the way in which she describes joining in with Hindley’s campaign of physical violence towards Heathcliff when he has been admitted to the household, revealing that she ‘plagued and went on with him shamefully’ along with Hindley, and subjected him to ‘pinches’. [10] This has led to some critics, for example the academics on the ‘In Our Time’ episode on the novel to somewhat simplistically label her narration as ‘unreliable’, which is, in my mind, a moot point.[11] Reliability, I would argue, is not something that we should be aiming for or looking for, especially from a first-person narrator, as though there is some ultimate truth to be found. Furthermore, what is so mysterious and evocative about this novel is that we don’t really ever see the full drama play out: we mostly hear about it through recounts of events from dishevelled and upset characters. The energy, however, is conducted through Nelly, who Bronte brings close enough to the core of the drama for them to be somewhat enveloped by the emotion, and at times becomes an active participant and instigator, but who is still able to contain the drama as a whole.

In all likelihood, Fennell’s adaptation will centre on Cathy and Heathcliff, indeed most of the press attention has already fixated on them. As a culture, we are strangely obsessed with their story, fascinated as we are with their wildness, their desire for the disintegration of their physical boundaries to become one ego (‘I am Heathcliff’) which, I reiterate, is a movingly adolescent perception of love and relationships.[12] This, in spite of the fact that Cathy dies around half way through the novel, and we spend as much time, if not more, with her daughter. As a side note, the opportunity to explore doubling and doppelgangers is ripe here, and I think that David Lynch could have made a very curious and provocative adaption of Bronte’s work. I really hope that Fennell uses the gifts of Lockwood and Nelly Dean to contain and conduct the narrative. Looking at the cast list, I am heartened and excited to see Hong Chau playing Nelly Dean, with a younger version of the character being played by Vy Nguyen. This is a casting choice that suggests that Fennell is offering a truly reimagined Nelly, taking us away from the staid matrons of old to give us a more dynamic character who more accurately reflects Nelly in the novel: a peer of the main protagonists alongside whom she effectively grows up.

There is no sign of a Lockwood yet; we can but hope.

[1] Wuthering Heights, Emily Bronte (London: Penguin 1985), p. 48.

[2] Ibid, p. 49.

[3] https://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=fuck%20boy accessed 15:03, 10/05/2025.

[4] Ibid, p.51; 53.

[5] Ibid, p. 74; p.191.

[6] Ibid, p. 49.

[7] Ibid, pp.71-71.

[8] Ibid, p.76.

[9] Ibid, p.220.

[10] Ibid, pp.78-79.

[11] https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/b095ptt5, 20:10 [accessed 14:50, 10/05/2025].

[12] Ibid, p.122.