We’ll always have Paris.

I have just returned from seven days in Paris and, predictably and gratefully, had a wonderful time. Prior to the trip, I concocted a three page day-by-day itinerary filled with activities, but also consciously carved out some time for some more spontaneous and impulsive things too (anxious traveller, moi? Absolutement).

August is a famously quiet time in the city because many of the locals go away on holiday. However, we found the first week in August to be a pretty excellent time to visit: our Eurostar tickets (booked in November) were £52 each for a return (less expensive than it is to get from Nottingham to London on the train…); certain museums in the city are free to enter on the first Sunday of the month and, because it was quieter, the queues were short (we managed the Musée de l’Orangerie and the Musée d’Orsay for free, but also available were The Louvre, the Musée National d’Art Moderne at the Centre Pompidou and many others); and going later in the summer meant that even with temperature highs of 29°C, we avoided the sweltering and sticky heats of June and July.

The benefit of spending a whole week in Paris is that we left barely any of the city unexplored. From our AirBnB base near the Place de Clichy in the 18th arrondissement, a delightful intersection of four arrondissements and in close proximity to my all-time favourites Montmartre and Pigalle, the whole city was at our fingertips. I would like to share some of my favourite places and moments from the trip. These may be food for thought if you are or intend to go to Paris at any point in the future, or if you just want to while away an afternoon thinking about those cobbled streets, beautiful buildings and all the amazing food. Like I will be.

Vegan food

Virginia Woolf’s old adage ‘One cannot think well, love well, sleep well, if one has not dined well’ is one that I take very personally, seriously and ecstatically live my life by. Therefore, first thing’s first: the food we ate. We did a lot of our own cooking to cut down costs, but we did have some fantastic vegan meals out:

Abattoir végétal

This is a lovely restaurant in the 18th arrondissement with a neon sign outside, fresh-feeling interiors and lots of hanging plants. They specialise in seasonal dishes, organically sourced food and organic wines by the glass and bottle. We went a couple of times to this restaurant and sampled the Green Augustine Buddha bowl of legumes, raw and cooked vegetables, smoky tofu and fresh leaves in a smoky balsamic glaze; the Funky Burger made with beetroot, vegan cheddar, pickles and sweet potato fries on the side; and the Hot without Dog made with falafel, grated carrot, red cabbage, ketchup, mustard and sweet potato fries. For dessert we had chocolate cake, and drank our way through both meals with a bottle of organic red. I couldn’t deal with it then, I can’t deal with it now. So much yumminess.

SO NAT – Notre Dame de Lorette

If I went into this trip sceptical about the tastiness of Buddha bowls and their capacity to actually fill you up, I stand completely surprised and corrected. The large Buddha bowls at this cute little café in the 9th arrondissement, down from Pigalle and just before Opéra, were delicious, hearty and required no emergency snack afterwards. My Buddha bowl contained breaded aubergine, pomegranate seeds, lentil dahl, all sorts of colourful veggies and leaves, vegan sour cream and red quinoa. It was ridiculous. MW’s had ginger, rice, BBQ tofu and, again, veggies on veggies on veggies. It was all fresh, came in big portions, was so healthy and tasted rich and delicious.

Maoz

One of the many amazing things we encountered on our trip to New Zealand last year was the healthy fast food franchise Pita Pit: a Subway of sorts that features meat but also specialises in falafel. Add to that some humus, pitta bread and multiple veggie accompaniments (lettuce, tomatoes, cucumber, red onion, carrot, sweetcorn, jalapenos, olives etc.) and you have the beginnings of an addiction. We visited roughly 15 over the course of six weeks and have no regrets. We have found nothing to compare in Nottingham, so when we found Maoz, a falafel and pitta shop, in the Latin Quarter, we were stupidly excited. The novel difference here? The assortment of Middle Eastern fillings (pickles, fatoush, salads, onions etc.) was presented as self-service. We had a joyful time stuffing our own pita pockets full to bursting with fresh, perfectly seasoned toppings. Maoz is unmistakeably a delicious, quick vegan lunch option, right next to Notre Dame Cathedral and Shakespeare and Company.

Bike Rental

In a city like Paris, tours of all shapes and sizes are prolific. We would have loved to have done a tour: I had high ambitions for some form of a champagne booze cruise. Alas, this did not happen but we were very much content to explore on our own. Holland Bikes are a well-reviewed tour and rental service in the city and around France, so we decided to use the Pick and Go service to rent two Dutch bikes from the Arc de Triomphe depot. Renting a bike is so much fun and you can cover so much ground in a short space of time. Plus, Paris has excellent infrastructure for cyclists and e-scooter riders, so despite the heavy traffic in parts (we categorically avoided the wacky races of Place de la Concorde and Étoile de Charles de Gaulle) it felt very safe getting around. We cycled from the Arc de Triomphe down to and around the Bois de Boulogne, then back up and around to Trocadéro, the Champs de Mars, Invalides and along the Seine. We had so much fun.

Parc Monceau

There are so many beautiful and shaded places to relax in Paris, which I am sure were absolutely essential during the 40°C+ heats the residents experienced this summer. The Place de Vosges in Le Marais came highly recommended, and we enjoyed the classic Tuileries gardens and Luxembourg gardens on the Left Bank. Whilst walking home on our last afternoon, we headed for the Parc Monceau which is in the 8th arrondissement, just off the Boulevard de Courcelles. Although the park has stylised elements like a little Venetian bridge, a Classical colonnade to emulate ruins and the most charming old carousel, there was something about more primeval about this park, compared to the more clipped and manicured lawns of the big jardins. We sat on a little green bench people-watching for a good long time in this prettyish wilderness.

Musée Yves Saint Laurent Paris

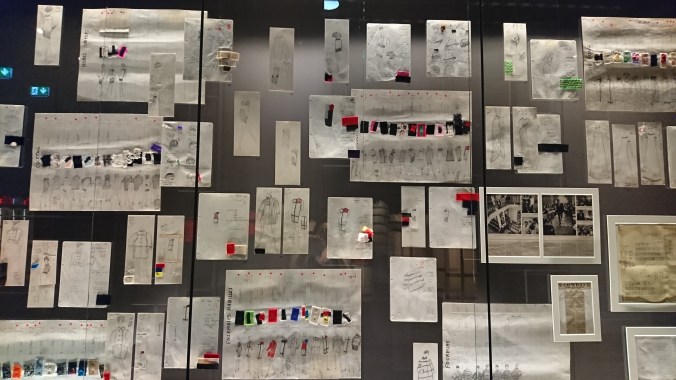

Oh boy. Pour moi, a trip to Paris was never going to be complete without a slice and dice of fashion history. I plan to write a longer post about the YSL Museum, but it’ll summarise it briefly here for now. Yves Saint Laurent never used to be one of my favourite designers; perhaps controversially, I have been more of a fan of the edgier Saint Laurent incarnation of the brand under Hedi Slimane and Anthony Vaccarello. I was, however, aware that he is an inescapable part of fashion history, after being made head of Dior at the age of 26 and for the successful couture house he built in his own right. What became clear to me from the exhibits in the museum was that, like Christian Dior (you can read my analysis here), Saint Laurent’s prime aim in design was to make a woman feel her most confident and beautiful. I find this to be such a validating and comforting thing. Even though fashion is so much to do with comparison, beauty standards, perfectionism, ageism, white and able-washing, what I have noticed is that oftentimes at the centre of a brand is a sensitive, empathic and deeply creative person who just wants to make women feel good. I really appreciate that in Yves Saint Laurent and his contributions to fashion. Furthermore, he was famously one of the first designers to champion the use of non-white models, pioneered the trouser suit and established his Rive Gauche collection to make fashions accessible and affordable to ordinary people.[1]

The building on the Avenue Marceau is home to his formidable archive, including the epoch-defining Mondrian dresses, the extensive jewellery collection and this absolutely perfect ensemble:

I was able to walk through a reconstruction of his study, watch films about his work and his partner Pierre Bergé and soak up the beautifully presented collection pieces. I must also add that the museum is wonderfully air conditioned, was relatively quiet and, all-in-all, a genius way of preserving Saint Laurent’s creative legacy.

Montmartre cemetery

This was a go-to last time we came to Paris and, being so close to our apartment, was definitively on our itinerary again. Cemetery-visiting may seem like quite a morbid activity, but I believe that visiting cemeteries helps to really contextualise a place and the people in it. To really know and understand a city and its different people, to get an insight into what they value, treasure and, ultimately, to understand their approach to living life, a clue can be found in exploring how they treat their dead and the way they design and use their communal and private spaces of remembrance and reflection. Even if we have not visited Paris, many people are aware that it is a city associated most commonly with love, art and revolution. This, I would argue, is reflected in their cemeteries, which are uniquely Gothic and gorgeous. There is a joie de vivre and gravitas evident in the Parisian cemetery, and Montmartre in particular, which makes it a space in which life, family and creativity are celebrated and revered. Of course, I couldn’t help thinking that it is only the wealthy and respectable who could have afforded such exuberant graves. Additionally, in no other cemetery have I felt that the burial of the dead is used to so confirm and validate the people left behind. It is in this capacity that I think gloom seeps into the cemetery: both in the potentiality that the wealthy dead were desperate to be remembered and that the living left behind were so desperate to build something in place of their lost loved ones.

Many famous people are buried in this city, and their resting places are free to visit and open for visitors to pay respects. Whilst Père Lachaise is one of the biggest and most famous- we saw the graves of Edith Piaf, Oscar Wilde, Jim Morrison and the Mauthausen Holocaust memorial- Montmartre cemetery is smaller and nestled into the Western corner of the village. Stretching underneath the Rue Caulincourt bridge, it is easily visible from the road and its fantastical rows of grand crypts and family sepulchres look like something from The Phantom of the Opera. We visited specifically to lay a rose at the grave of Vaslav Nijinksy, the lead dancer of the Ballets Russes, choreographer of The Rite of Spring and, I recently found out, a passionate vegetarian. I have mentioned here before that The Rite of Spring has been a very important piece of music and dance to me, and I wanted to show my gratitude to this extraordinary sensitive and surreally gifted man who helped collaborate on and create such an awe-inspiring piece of cultural history.

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/projects/cp/obituaries/archives/yves-saint-laurent-models-couture [accessed 14:41, 13th August 2019].

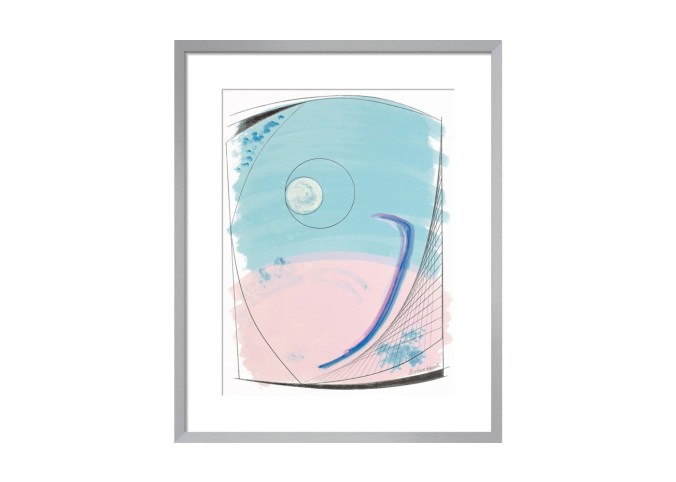

My dad had also instilled in me an appreciation for Anish Kapoor, whose Sky Mirror is pride of place outside the Nottingham Playhouse theatre, and who created a rusty horn bursting out of the immaculate gardens of Versailles in 2015:

My dad had also instilled in me an appreciation for Anish Kapoor, whose Sky Mirror is pride of place outside the Nottingham Playhouse theatre, and who created a rusty horn bursting out of the immaculate gardens of Versailles in 2015: