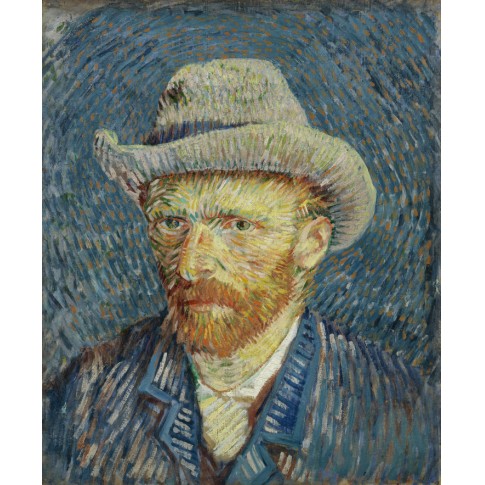

AKA men who look at the stars

Last Thursday, I went to see the touring production of Les Misérables at the Palace Theatre in Manchester. In a signature Elizabeth Harper move, I bawled my eyes out pretty consistently throughout the entire production [SPOILER ALERT]: during ‘I Dreamed a Dream’, ‘On My Own’, when Gavroche was shot, when Éponine was shot, when Enjolras was shot, when Marius sings ‘Empty Chairs at Empty Tables’ and, finally, during Jean Val Jean’s death with the lyric ‘To love another person is to see the face of God’. I’m not a Christian, but I just think that is the most beautiful idea: there is something spiritually transcendental about loving another human being from your very core.

Turning into a weeping willow aside, I enjoyed Les Misérables because I got to see one of my favourite characters being performed in the flesh: Inspector Javert, who sings ‘Stars’, my favourite song in the musical.[1] Javert reminds me of another of my favourite male characters, who I like for very different reasons but, incidentally, also has a beautiful and interesting relationship with the stars. I am going to offer a short and snappy comparison between Inspector Javert and Alyosha Karamazov from Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov.

On a very basic level, I want to sit Javert down and tell him that everything is going to be OK and that he just needs to ease up on life. For those who are not familiar with the story, Javert is born in jail to parents embroiled in poverty and crime and raises himself in life through his dedication to the law and authority. He becomes obsessed with Jean Valjean, who, in Javert’s singularly black and white worldview, is a thief and an inherently ‘bad’ person. Javert looks to the stars as his guiding lights of order and control within the chaos of revolutionary France, and of his own personal history:

‘Stars

In your multitudes

Scarce to be counted

Filling the darkness

With order and light

You are the sentinels

Silent and sure

Keeping watch in the night

Keeping watch in the night

You know your place in the sky

You hold your course and your aim

And each in your season

Returns and returns

And is always the same

And if you fall as Lucifer fell

You fall in flame!’[2]

Click here for Philip Quast’s rendition of the song:

He sees stars as pinpricks of certainty, surrounded by a dark, unknowable vastness. He is invested in certainty, predictability, of a specific and very dichotomous construction of what is ‘good’ and ‘bad’. He perceives Jean Valjean as Lucifer: a rebel, a traitor, and someone who must be brought to justice. In his search, he is unrelenting, and has no room for mercy or any sense of moral ambiguity. I find Javert so endearing and interesting because he believes completely and utterly that order and control are what keep himself and the world a safe and just place. As a character, I think he speaks to anyone who, at one point or another, has believed that ‘being good’ has in some way protected them from the storminess of life and the people within it. Certainty, however, is an illusion. It is his inability to accept that life is impermanent, fluid and precisely uncertain that leads to his loss of faith: in, what is for Javert, an unprecedented act, Jean Valjean spares his life, thereby undercutting the embodiment of ‘badness’ that Javert has spent decades projecting onto him. It leads to Javert in turn sparing Jean Valjean’s life, which he cannot fathom, he cannot reconcile with:

‘I am reaching but I fall,

And the stars are black and cold,

As I stare into the void, of a world that cannot hold.

I’ll escape now from that world;

From the world of Jean Valjean.

There is nowhere I can turn. There is no way to go on!’[3]

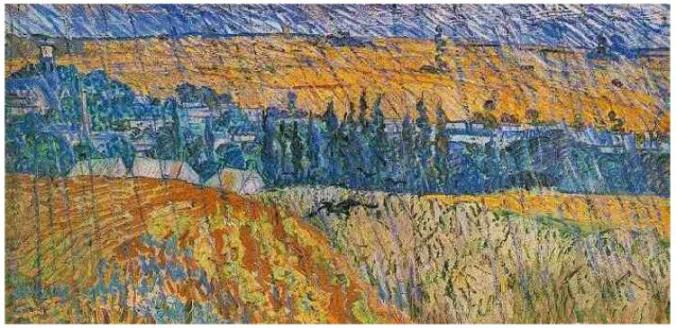

The world of Jean Valjean is a world of disorder and chaos that overwhelms Javert. He feels abandoned by the stars, consumed by the darkness that he has kept at bay all throughout his life by being so devoted to a very literal interpretation of law and order, good and bad. This, eventually, leads him to take his own life. Interestingly, he does this by throwing himself into the running waters of the Seine, the river being a stark embodiment of the fluidity and tumult that Javert could not accept.

Alyosha Karamazov, on the other hand, rediscovers his faith and love for all of humanity through looking at the stars. His spiritual guide and mentor, the Elder Zosima, dies midway through the novel. His corpse begins to rot, which sends shockwaves throughout the monastery: the superstition is that a truly holy man’s corpse would not rot, but would instead stay pristine and intact. Young and still slightly naïve, Alyosha is swayed by the mutterings of his fellow monks, and begins to doubt the spiritual integrity of the Elder Zosima. Throughout the novel, Alyosha is presented as a character whose goodness, his joy and his desire to help the flailing and chaotic people around him are all expressed through his face. If you’re interested, this essay (‘The Faces of the Brothers Karamazov’) is a brilliant summary of the various faces within the novel. One of Alyosha’s faces that the writer of this essay doesn’t mention, however, is Alyosha’s face after the rotting of the Elder Zosima’s corpse. Where his face is closely related to beauty and youth before this point, it changes, at what the narrator refers to as a ‘critical moment’:

‘Alyosha suddenly gave a twisted smile, raised his eyes strangely, very strangely, to [Father Paissy] the one to whom, at his death, his former guide, the former master of his heart and mind, his beloved elder, had entrusted him, and suddenly, still without answering, waved his hand as if he cared nothing even about respect, and with quick steps walked towards the gates of the hermitage’.[4]

In this moment of doubt, which is confirmed as such in the next chapter by the narrator, Alyosha’s normally bright and entreating face becomes different, almost cynical and manic. To see someone described as almost angelic become ‘strange’ signifies an unnerving change in the character. In a novel where much of the action involves the men of the Karamazov family passionately rushing about with Alyosha in their wake trying to tie up all the loose ends, here we see Alyosha himself caught in a storm. This is further emphasised by the uncomfortably long sentence, broken apart by commas, almost as if the words are panted with the effort of hurrying.

Yet, it is the stars that help Alyosha to re-discover his faith, hope and love for life and all of humanity. The following is one of my favourite pieces of writing I’ve ever read. Gear up, it’s a long one:

‘Filled with rapture, his soul yearned for freedom, space, vastness. Over him the heavenly dome, full of quiet, shining stars, hung boundlessly. From the zenith to the horizon the still-dim Milky Way stretched its double strand. Night, fresh and quiet, almost unstirring, enveloped the earth. The white towers and golden domes of the church gleamed in the sapphire sky. The luxuriant autumn flowers in the flowerbeds near the house had fallen asleep until morning. The silence of the earth seemed to merge with the silence of the heavens, the mystery of the earth touched the mystery of the stars… Alyosha stood gazing and suddenly, as if he had been cut down, threw himself to the earth.

He did not know why he was embracing it, he did not try to understand why he longed so irresistibly to kiss it, to kiss all of it, but he was kissing it, weeping, sobbing, and watering it with his tears, and he vowed ecstatically to love it, to love it unto ages of ages. “Water the earth with the tears of your joy, and love those tears…,” rang in his soul. What was he weeping for? Oh, in his rapture he wept even for the stars that shone on him from the abyss, and “he was not ashamed of this ecstasy.” It was as if threads from all those innumerable worlds of God all came together in his soul, and it was trembling all over, “touching other worlds.” He wanted to forgive everyone and for everything, and to ask forgiveness, oh, not for himself! but for all and for everything, “as others are asking for me,” rang again in his soul. But with each moment he felt clearly and almost tangibly something as firm and immovable as this heavenly vault descend into his soul. Some sort of idea, as it were, was coming to reign in his mind-now for the whole of his life and unto ages of ages. He fell to the earth a weak youth and rose up a fighter, steadfast for the rest of his life, and he knew it and felt it suddenly, in that very moment of his ecstasy. Never, never in all his life would Alyosha forget that moment. “Someone visited my soul in that hour,” he would say afterwards, with firm belief in his words…’[5]

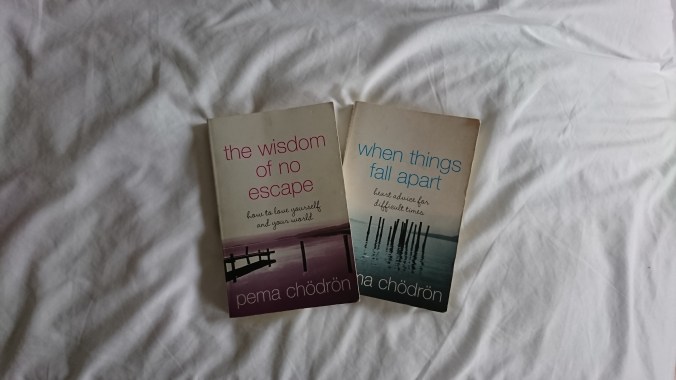

Where Javert lost his faith in order and the dichotomy of ‘good’ and ‘bad’, the stars for him turning into a great void of chaos and confusion, in The Brothers Karamazov, Alyosha is humbled and overcome by the joy of life because of the stars. Under the celestial wonder of the Milky Way, Alyosha comes to understand and appreciate the depth and beauty at work in every human being. Whilst Javert is consumed by the abyss, Alyosha cries with joy, ‘even for the stars that shone on him from the abyss’. Furthermore, where Javert throws himself into the waters of the Seine, Alyosha accepts the uncertainty and ecstasy of a life of difference and love, and throws himself to the floor, finding himself on solid ground. It is this paradoxical acceptance of uncertainty, chaos and tumult that helps Alyosha to find a sense of stability, and of his place in the world. Ultimately, and again unlike Javert in the most tragic sense, Alyosha’s reconciliation with mystery and ambiguity leads him to a place of forgiveness and gratitude. It brings him to love himself and all of mankind, no matter what has been done or whatever will be done. It is a moment of irreverence, peace and boundless love, steeped in the wonder of living life hopefully. In short, a piece of writing everyone would do well to keep in mind.

These men remind us that in looking at the stars we have a choice about how we perceive ourselves, our place in the world and, indeed, the universe. Javert’s story is poignant in its tragedy; Alyosha’s for its eruption of joy. Carl Sagan said that ‘we are a way for the Cosmos to know itself’: these two beautifully crafted characters, in their relationship to the stars above them, provide two compelling and very moving blueprints. In the musical and in the novel, we see them play out the archetypal human experience of living with uncertainty and mystery in their own very different but no less endearing ways.

[1] My assessment of this character has purely come from the way in which he is portrayed in the musical version of the novel (I will get round to reading it at some point) but considering how well-loved and culturally important the musical is, I think that is enough.

[2] ‘Stars’, Les Misérables, Claude Michel Schonberg / Alain Albert Boublil / Herbert Kretzmer

[3] Ibid.

[4] The Brothers Karamazov, Fyodor Dostoevsky transl. Larissa Volokhonsky and Richard Pevear (London: Vintage Books, 2004), p.337.

[5] Ibid., p.362-3.