This article is dedicated to Charlotte Bender, Francesca Bender and Hanan Isse: my fellow obsessees

Video essayist Broey Deschanel recently posed the question: ‘Have We Grown Out of Gossip Girl?’ By looking at the class, gender and racial politics of the show, and the wider politics and issues with re-makes, her answer is an unequivocal and undeniable: yes. Whilst aesthetic nostalgia for Gossip Girl is high (because who wouldn’t want to eat lunch on the steps of the Met or venture an embellished headband?) it is a show that does not need resurrecting or an attempt at correction. Her analysis that Gossip Girl sided with elites, demonising working class characters, catching principled characters into a tangled web of deceit and selfishness whilst glorifying toxic chauvinism (Chuck sells Blair for a hotel), demonstrates that Gossip Girl is a show too riddled with the white supremacist hyper-wealth orthodoxy of its time to be worth redeeming.

The show is almost a historical artefact of capitalism’s anaemic attempt at self-criticism, eventually reinforcing itself and seducing everyone in its wake, characters and viewers alike, when arguments for capitalism were becoming increasingly tenuous in the context of recession, economic suffering and burgeoning inequality. This would go on to lay the groundwork for a subsequent decade, and counting, of austerity in the West. No amounts of references to F Scott Fitzgerald’s The Beautiful and Damned, Serena Van Der Woodsen’s favourite novel, could distract us from class-bashing snobbery, rampant aspirationalism and full-bodied immersion and defence of white privilege and supremacy.

Ironically, we are living in a time of studios hyperactively re-making, sequelling and prequelling everything: capitalism is so desperate to reinforce itself to itself and ensure a buck, that it cannot stomach the risk of making something new. I wrote about this in 2014 and there are signs that things are beginning to change. With the emergences of more experimental forms of television storytelling such as Master of None, Fleabag, I May Destroy You, Pose, The Politician and The Good Place against the backdrop of a larger appetite for non-white heteronormative stories centring around race, sexualities, genders and philosophies that have been previously untold in a popular way, we are seeing progressive shifts that render the prospect of shows like Gossip Girl more and more redundant. It has been particularly promising this year to see the number of films and TV shows exploring stories of race and class being feted and nominated for awards, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom and Malcolm and Marie forming two of my favourite films so far, even if the jangling of white supremacy still echoes and reverberates throughout the creative industries (no Golden Globe nomination for I May Destroy You?)

So, where can we go for an aesthetically-fuelled glossy teen melodrama? Is there place for such a thing in the twenty first century?

My answer: yes. Do I want to see well-dressed people getting into romantic dilemmas, going on coming-of-age adventures, disappointing people around them, ripping up expectations, finding their voices, breaking up and making up and all set to a fabulous soundtrack? Yes. Whole-heartedly. But it goes deeper than that. This need for stories about teenagehood reminds me of Frank Wedekind’s Spring Awakening, a late nineteenth century German play that sought to express and plug the gap in stories for and about teenagers to navigate the upheaval of adolescence. The play, scandalous at its first performance, covers sexual repression and expression, abuse, suicidal depression, homosexuality and the relentless pressure of morality and achievement in arbitrary school exams: issues that still feel relevant and familiar to teenagers now, with a quintessentially new iteration of perfectionism that entails a life lived through the filters of social media. This rite of passage has been maligned throughout much of Western history, with teenagers demonised and ridiculed for the seismic shifts they experience in their bodies and identities, without any kind of holistic guideposts to nurture and respect them through it. Our experiences as teenagers lay the groundwork for our future relationships with ourselves (and our therapists) and, as explored so well in the documentary Beyond Clueless, secondary school is a charged space to explore a heady mixture of emergent and predominant ideas, with the teenage body a soil, in its perpetual state of flux, expansion and contraction, to do this. I don’t spend my time watching back-to-back teen shows or teen films because the chaos of melodrama and angst no longer feels like an outward projection of my own internal tumult. But I continue to hold the genre in high regard, in much the same vein as Mark Kermode in his advocacy for the Twilight franchise. If we are to live in a society where teenagers are not honoured, then why should we damn genres that appeal and speak to this dramatic, archetypal experience that they are going through? Whether we have anonymous whistleblowers and gossip mongers, vampires or quixotic righteous dudes, teen films and shows are crucibles and allegories for bigger shifts, both personally and societally that are, whether they mean to be or not, both vitally hyperbolic and fascinating. In the case of Gossip Girl, it turns out, we should have been paying more attention.

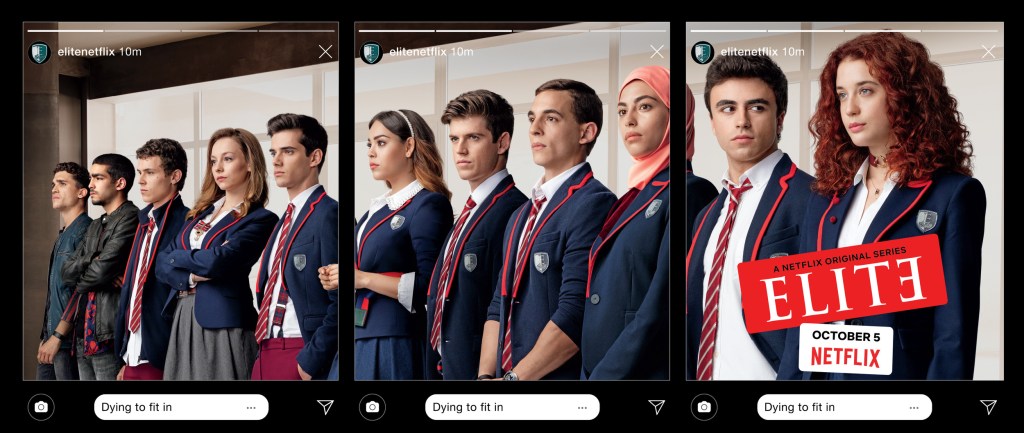

As such, we don’t need a new Gossip Girl or, god-forbid, the re-make of Clueless that we keep getting threatened with (the original should remain an untouched gem and deserves respect and adulation not an irrelevant, fatigued re-make). We already have a show that is compelling, compulsive, aesthetically pleasing and playing whack-a-mole with big teenage issues in a critical and entertaining way. Crucially, it also grapples with many of the issues that a new Gossip Girl may want to rectify and reconcile with to itself, which Broey Deschanel predicts will be watered down and disastrous. Issues like race, religion, sexualities and deconstructions of class power structures. My friends, I give you, Netflix original series, Élite.

Élite’s premise seems standard fare: told in flashback, three working class students are given scholarships to shiny, international, private school, Las Encinas, located in an ambiguous area of Spain, but most likely near Madrid. The scholarships are a form of compensation from the rich owner of a building company, who built a structurally inadequate state school that collapsed. The son of the owner of the building company also goes to Las Encinas with his extremely wealthy and aristocratic friends: immediately, as a result, there is discord, resentment and rivalry between the two groups. The backdrop of all of this is a murder investigation, as one of the students is found dead next to the swimming pool at Las Encinas. A heady mixture of Big Little Lies, Skins, Cruel Intentions and, yes, Gossip Girl, it is immediately aesthetically pleasing and riveting. At the very least, along with the rollercoaster ride of dramas and chaos, viewers have the additional pleasure of having learned a variety of Spanish swearwords. And the background reggaetón is always on point.

Without spoiling anything, the show deals with a plethora of teen issues: the standard first sexual experiences, family fall outs, teen pregnancy, ambition and inter-class/clique warfare. Additionally, there are higher stakes of HIV diagnoses, cancer diagnoses, threesomes, throuples, incest, blackmail, revenge porn and drugs thrown into the mix. In short: a whole lot of loco. Across the seasons, however, Élite goes on to explore the intersections of many of these issues in greater depth, most powerfully, the immigrant-working class experience and, in particular, the cultural tensions of growing up Muslim in the West. This includes relationships between faiths, homosexual relationships (the cutest gay couple ever has to be Ander and Omar), the politics of feminism and the hijab, and both subtle and overt forms of anti-Muslim hatred. We have rarely seen a character like Nadia presented on television and it is joyful to watch her unfolding across the seasons.

Even the intersections and illusions of wealth are explored: the differences between no money, new money and old money, with most of the judgment and consternation reserved for the aristocrats. Unlike Gossip Girl, the most despicable characters in Élite are the privileged who lie, cheat and betray others to maintain their social position, closing ranks and perverting justice through their family names and wealth. Self-preservation is constantly at work in Élite: this manifests as working class characters attempting to reject and resist the trappings of wealth and privilege to preserve their sense of dignity and self-respect; whereas, the wealthy pull up their drawbridges and manipulate the power structures to get their own way. They become unredeemable in the process. Yet there are some who do change, and there are some divine redemption arcs at work, the best I’ve seen since Steve Harrington in Stranger Things.

As such, where Broey Deschanel’s criticism of Gossip Girl focuses on the fact that everything, including the viewers, is subsumed by the inordinate toxic influence of power and privilege, in Élite, a form of equilibrium and, dare I say, comradeship between the classes eventually emerges. Of course, we are still based in a powerful, private school only accessible to the privileged few; but it feels like the upper classes are the ones who have had to adapt and give up something, in the form of their power and privilege, in order to survive and not the other way round. The only question that remains, as Season 4 approaches, is whether this will be maintained. My main criticism is that even with the introductions of Yeray and Malik in Season 3, there is plenty more space for black characters in the show, and I think the show has great potential in posing more questions on race. Needless to say: we don’t need a re-make of Gossip Girl. Élite is the show Gossip Girl should have been ten years ago, and I for one think we all need more of it.

Full disclaimer: I watched all three seasons of Élite during Lockdown 1.0 and it definitely became an emotional crutch when many of us, myself included, seemed to regress into a state of teenagehood, confined as we were to our rooms for months on end (explored so well in this article). If there is anything I need to add or qualify, let me know.