Part Two: Tarantino’s representation of women

To continue my exploration of expectation in Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon A Time… in Hollywood, (my critique of the ranch scene can be found here) I would like to discuss an aspect of the film that received a lot of traction in the run-up to its release and occupied commentators afterwards.

During the film’s promotional tour at Cannes Film Festival, a clip from Once Upon a Time’s press conference went semi-viral. It featured a journalist asking Quentin Tarantino about Margot Robbie, having been in films such as The Wolf of Wall Street and I, Tonya being given few lines as Sharon Tate in this film. The clip can be seen here. Tarantino unequivocally ‘rejects [the] hypothesis’ and Robbie answered that she ‘appreciated the exercise’ of using alone-time on screen to construct a character as opposed to being presented always in relation to or through interaction with others. This did little to convince some commentators upon the film’s release, including Clémence Michallon at the Independent, who concluded that Tarantino’s lack of dialogue for Robbie was indicative of Tarantino’s male gaze subsuming everything, which was both ‘insulting’ and ‘boring’.[1]

This has been a sticky issue in my thinking about the film. I am, as many of you aware, a big advocate for women being given nuanced, interesting characters in film. Having said that, I am not a strict disciple of the Bechdel Test, whilst I appreciate its importance as a basic bar for storytelling and representation on-screen.[2] (For the record: this film does pass the test). I really enjoyed Once Upon A Time… in Hollywood, but it’s true that Robbie does not say much and this is slightly uncomfortable: Sharon Tate does little more than put music on, drive around in a delightful Porsche and dance about. I can absolutely appreciate the criticism; however, I think this is, ultimately, a simplistic argument, given the self-reflection at work in the film and because of the way in which Tarantino uses the film and its setting to play with history and expectation.

Similarly, I think it is important to highlight that having dialogue in a film does not necessarily save women from poor representation (see my footnote on the Bechdel test). The journalist at Cannes suggested The Wolf of Wall Street as a film where Robbie was given plenty of dialogue to work with, and yet Martin Scorsese’s representation of her was sexualised beyond belief. Robbie was front and centre of Suicide Squad as Harley Quinn, and yet here too she was hyper-sexualised and Zac Snyder gave her little to work with beyond that. Michallon at the Independent makes the case that in Once Upon a Time, Tarantino uses Robbie as Sharon Tate to convey a deified form of femininity: ‘a luminous, kind, generous angel of a woman whose heart seems wide open to the world. It’s a flattering depiction, for sure, but it’s also terribly reductive […] a lifeless, perpetually cheerful doll’. I would argue, in the first instance, that the fact that we see these former attributes as reductions is a damning indictment both of the nastiness we tolerate in society and the way in which we accept being open-hearted and kind as completely unrealistic. Sharon Tate was described with reverence by the likes of Mia Farrow and was famed for her generosity and kindness, there is no reason why this should not be significant in Tarantino’s representation of her here. Secondly, I would like to argue that through the film’s use of history as a fluid play-thing, Margot Robbie and Sharon Tate were not reduced within the narrative of the film, and that in more ways than focusing on one female character, Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood waves in an empowered cohort of women and womanhood.

One of the most important parts of Michallon’s argument is that Tate does not experience any kind of personal growth and that ‘watching people just live is boring’. Of course, this is an extremely personal assessment: I happen to be an enormous fan of films where not a lot happens and what we are offered is an in-depth character study. What is so ironic about this claim, however, is that in real life, we cannot watch Sharon Tate live and we haven’t been able to since 1969. This is singularly important in the film. We might complain that not a lot happens because she spends a day on her own and she doesn’t talk to anyone, but there is some joy in watching a woman on a solo trip to the cinema (an exercise I would recommend all women indulge in/challenge themselves to at one point or another), enjoying time with her friends, dancing and having fun and preparing for motherhood when we know in real life that Tate was robbed of the chance of being able to do this. Furthermore, we are offered nuance in the dialogue-less-ness: in her interaction with a female hitchhiker, Tate drops off the woman, wishes her all the best on her ‘adventure’, thus suggesting that she spent the majority of the journey listening to someone else’s story; we are offered actual footage of Sharon Tate in the cinema that Robbie’s Tate watches, forming homage, an opportunity for self-reflection and, for us, a melancholy funhouse mirror of reality. It is an echo of the fact that this film plays with history, something that will be completely apparent by the end of the film. Alternatively, although Tate is depicted as loving and loveable, the interpretation can be made that she displays smugness, vanity and happy-go-lucky privilege in her life as a white, blonde, beautiful woman; a kind of flip-side to the open-heartedness and generosity that some find so problematic. One way in which I think the film could have been improved is if Tate had had some kind of hand in killing the hippies in a badass, heavily pregnant way. And yet, just maybe, the best thing to do for a character who in life was a victim to such appalling violence, was to keep her removed from it.

This is where bittersweetness seeps into the film: we know that in real life, she does not survive that night in 1969, and neither do her friends. When she offers Rick Dalton the opportunity to come into her house after the pool party of hippy carnage and the end titles begin to materialise on-screen, we know that we have reached the fairytale territory that only Hollywood can give us.[3] Primarily, it is Tate in the position of power: she is the one who could be a useful contact for Dalton, who spends most of the film choked up and flailing about, and not the other way round. She is the valuable, influential and powerful contact to have in the industry, not the male television star. Additionally, and similarly to seminal Tarantino revenge film Inglourious Basterds, which re-writes the history of the Second World War with Hitler and his cronies getting an epically fiery bloody death at the hands of escaped Jew Shosanna, in Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood we are offered an alternative reality where Charles Manson’s blood-thirsty hippies don’t butcher Sharon Tate, but get their comeuppance at the hands of Brad Pitt and a cute dog, and Sharon Tate herself is in a position to offer help and support to Rick Dalton in the loving and kind way that we have come to expect from her. Tarantino offers us a moment where history was very different: where bad guys are punished, the good survive and everything should have been OK.

And yet, despite the satisfying end that is put to the hippies, the heroics of Cliff Booth and his dog and the hilarity of the flame-thrower in the garden shed, the ending here is poignant and sad, as opposed to the jubilation and bad-assery of Inglourious Basterds . The camera lingers on Tate, Dalton and Tate’s friends from afar, as they introduce themselves and discuss the attack. Their conversation is barely audible, and the camera stays put, almost from a high CCTV angle, as they slowly follow one another into Tate’s house. A lot of space is created between the actors and the camera and, ergo, the audience watching. It enables us to sit within this strange liminal space where we can enjoy and revel in what we have just witnessed; but the distance cultivates a sense of knowing; a knowing that this did not happen. Tarantino wrote that Sharon Tate stayed alive and continued to live her beautiful life, but we know that she didn’t, murdered as she was in the most horrifying and violent way. Pertinently, the camera then stays on Tate’s Porsche and the other cars they have in the driveway, using the visual metaphors to reflect the power of the Hollywood machine to re-write and re-create things as we want them to be. Hollywood is itself a vehicle for change, for creativity and for embracing life over destruction; or, at the very least, offering the façade of that. It has a twofold power to reflect change and to exact change; to re-write history but also to ensure that the future is safeguarded. Ultimately, in this case, Sharon Tate can only stay alive in the movies.

Hollywood’s role in the film is developed and explored in numerous parts of the film, in particular with regard to the representation and role of women. Importantly, and as mentioned in my critique of the ranch scene, Cliff Booth does not have sex with Pussycat, the underage hitchhiking hippy with impressive underarm hair, in his car. This is not what she expects or, perhaps, what the audience may expect, particularly as this is a dynamic that has pervaded the film industry for as long as Hollywood has been functioning. Harvey Weinstein was a producer and collaborator with Tarantino for every single film he has written and directed, so the significance of this scene cannot be overstated.

Similarly, one of the shining stars of the film comes in the form of Trudi, played by the delightful Julia Butters. At only 8 years old, Trudi almost steals the film and her character is one of the standouts amongst a cast of standout performances. Her endearing and academic approach to the craft of acting is refreshing, powerful and leaves Leonardo DiCaprio’s Rick Dalton’s a gibbering, insecure wreck. Indeed, his entire self-worth on the set of the Western they are shooting together boils down to what Trudi thinks of his performance and his ability to achieve the performance, in particular through knowing his lines. In the scene where he gives himself a rollicking in his trailer, he mentions Trudi, berating himself to not show himself up in front of her. She, because of her commitment to her work, her ability to interpret and understand story, her thorough approach to research and her interest in the wider industry, is made out to be a force to be reckoned with. As with the subversive ranch scene, where Tarantino constructs the difference between psycho-killer hippies and the misunderstood, kooky youth, and thereby critiquing snowflakism, in Trudi we see the highest hope for future generations in film and beyond: doing their research, speaking their minds and not limiting themselves to who they think they should be. At the end of a long scene they shoot together, Trudi, who we know at this point Dalton completely respects and admires, tells him that he just put in the best acting performance she has ever seen, and Dalton immediately chokes up. His belief in himself completely stems from the way in which he is perceived by this precocious, wise and talented young girl and he can barely contain his emotion at having shone in her eyes.

As such, I believe that the argument that women are reduced in this film is not a very convincing one. Sharon Tate does not speak much in the film, it is true; but her role in the film, sensitively portrayed with the respect of Tate’s family in mind as much as for Tate herself, is to celebrate life and the power we have to construct our own narratives. If she had been killed at the end, then she would truly have served as a lifeless doll; but she lives, and she is glorious. She is not part of the overall plot because the plot is about two menopausal men trying to stay relevant. Robbie’s Tate does not have that concern and has ample time to while away the time, with added luxury of being on her own, both during the film and, thanks to the film’s revision of history, we can assume after the credits have rolled. To compound this, we have Trudi, a bright spark for the future who has plenty to teach the struggling Rick Dalton; and a man in Cliff Booth who respects the boundaries of power, age and experience by not taking advantage of a young girl. Tarantino has never shied away from giving audiences strong female characters, but in Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood he provides a much more subtle offering, playing with our expectations and using a variety of characters and dynamics to do a great justice to the women of the film and the actors who play them.

[1] ‘Quentin Tarantino’s male gaze in ‘Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood’ isn’t just insulting – it’s profoundly boring’, The Independent https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/features/once-upon-a-time-in-hollywood-quentin-tarantino-sharon-tate-margot-robbie-lines-a9061446.html [accessed 12:05, 19th August 2019].

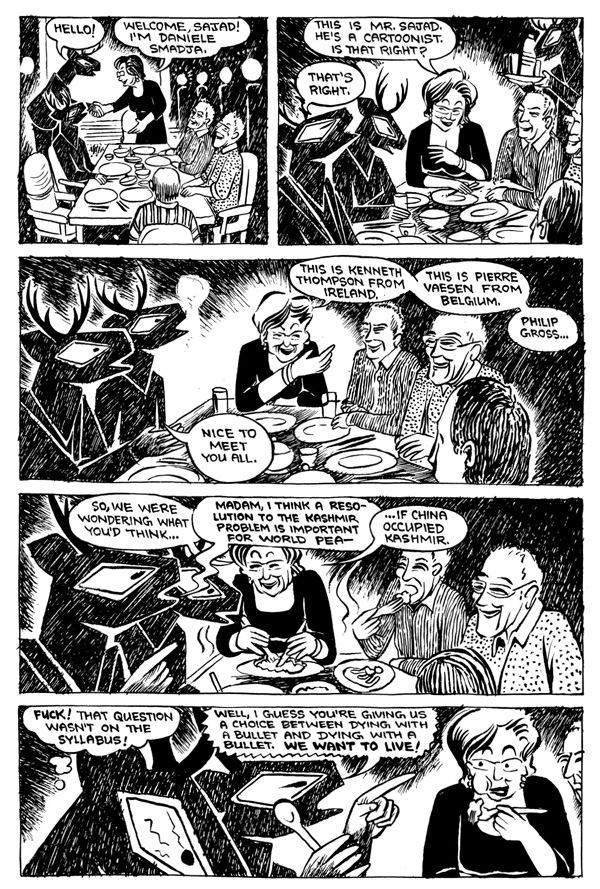

[2] The Bechdel Test, created by Alison Bechdel, suggests that to pass a basic representational threshold, films must have more than one female character, the female characters must speak to one another and the female characters must speak to each other about something that does not involve a man. Of course, many culturally celebrated films do not pass this test, but then neither do films like Gravity, A Star is Born and Arrival, in spite of the lengthy screen-time afforded to women and where the quality of the female characters is exceptional. Equally, there are many female-centric films where women have plenty of dialogue and on-screen time, but their lives and conversations revolve around men.

[3] I want to add here that the irony of Dalton proclaiming earlier on in the film that he is ‘one pool party’ away from Roman Polanski and then fighting a hippy with a flame thrower in his pool becoming his ticket to friendship with Tate, is just hilarious.